Last summer, I stayed at the Hotel Albrechtshof in Berlin-Mitte, formerly East Berlin. In a corridor, I noticed framed black and white photographs of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in East Berlin. The date was September 14, 1964. I had never seen these photos before nor had I heard of Dr. King’s visit to East Berlin. How was that possible? When President John F. Kennedy went to West Berlin a year earlier, his visit made headlines around the world.

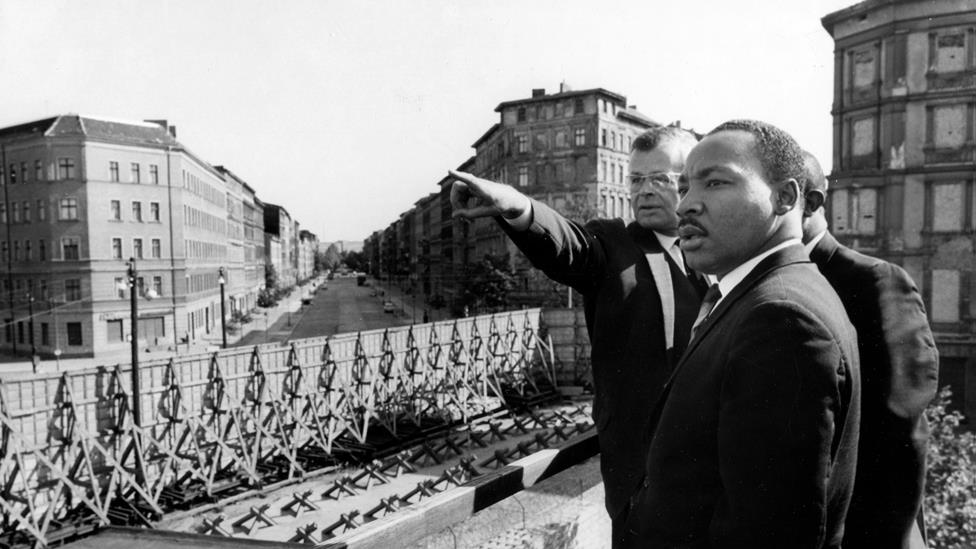

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Berlin in 1964 Source: Getty

Unlike JFK and other American leaders, Dr. King did not only speak in West Berlin but crossed the Wall into East Berlin, the capital of East Germany. At a time when East Germany was not yet officially recognized by the United States or by West Germany, this was a radical move. Perhaps that is why Dr. King’s speeches in the divided city barely made a ripple when they happened and have pretty much been ignored since then.

In 1964, the Cold War was hot. Ideologically, politically and militarily, Europeans and Americans had divided the entire world into two hostile and opposing camps. West vs. East was shorthand for United States vs the Soviet Union and that stood for capitalism and democracy vs. communism. Politicians, scholars and journalists on both sides of the divide saw even remote regional conflicts and events in terms of this larger dichotomy of Good Empire vs. Evil empire. By the time Dr. King visited Berlin, the Cold War was almost twenty years old and people had accepted the Balance of Terror as the new World Order. In heated and often simplistic ideological rhetoric, politicians in East and West condemned the other side as illegitimate and immoral. If the Cold War had a bull’s eye, it was the divided city of Berlin. When Dr. King arrived there in 1964, the Wall had been in place only three years. Berliners on both sides were still jittery because they didn’t know what the sealed border would mean for their lives. Reports of attempted escapes across the Wall headlined West Berlin’s daily papers. Only a day before Dr. King’s visit, an East German was shot for swimming West across the Spree River and the incident all but turned into an East West confrontation.

In East and West, Germans of all ages revered Dr. King for his leadership in the Civil Rights movement and West Berlin Mayor Willi Brandt welcomed the outspoken minister in his island city. Dr. King’s was in Berlin for only a day and a half and his itinerary was jam-packed. In the morning, more than twenty thousand West Berliners came to hear him at the Berlin Philharmonic Hall where he opened the 14th Annual Cultural Festival with a Memorial Service for John F. Kennedy. In the early afternoon, Dr. King delivered a sermon at the annual gathering of West Germany’s Protestant Churches in the open air Waldbühne amphitheater (which attained notoriety less than a year later, when it was ransacked during a Rolling Stones concert by ecstatic fans). Right after his sermon, Dr. King was awarded an honorary degree by the Theological School of the Protestant Church. Then, the American visitor went to see the Wall.

He had been invited to speak in the Marienkirche, a Protestant Church in East Berlin, but the American Embassy had confiscated his passport to prevent him from crossing the Wall. The civil rights leader was not deterred. At Checkpoint Charlie, his limousine approached the border guards, who recognized the famous civil rights leader, heralded in East Germany’s daily newspaper as a leader of “the other America.” They let Martin Luther King pass without a passport when he showed them an American Express card for identification. I’ve personally experienced the tight security at East German checkpoints many times, so I had a hard time believing this, but German and US sources corroborate the story. It’s still not clear to me who actually invited Dr. King to East Berlin. We know that there was no announcement of his visit in the media. A small sign next to the front portal of the Marienkirche church named him as the evening speaker. East Germans were eager to hear the man who stood for civil and human rights and for freedom. By the time he arrived, the Marienkirche had filled up and hundreds of East Berliners patiently gathered outside. So as to not disappoint them, Dr. King agreed to deliver a second sermon at the Sophienkirche, which was also packed when he got there. He did all that in one day. Before he had to return to West Berlin at midnight, he agreed to meet with members of the Protestant Church of East Germany in the Albrechtshof which is now a hotel. That’s why those photos were hanging in the corridor.

The very fact that Dr. King went to the East during this time of absolute polarization riled political commentators. No mention of his visit was ever made in the East German press, probably because his message of liberation did not fit with the immediate political agenda. Western media mentioned Dr. King’s Berlin visit to East Berlin and then allowed it to disappear, probably because it amounted to a legitimization of East Germany.

To me, Dr. King’s visit is audacious because the minister broke the unspoken rule that required public figures to follow the Cold War language of division and separation. Here are excerpts from his speech:

I come to you not altogether as a stranger, for the name that I happen to have is a name so familiar to you, so familiar to Germany, and so familiar to the world, and I am happy that my parents decided to name me after the great Reformer. I am happy to bring you greetings from your Christian brothers and sisters of West Berlin…

Certainly, I bring you greetings from your Christian brothers and sisters of the United States. In a real sense we are all one in Christ Jesus, for in Christ there is no East, no West, no North, no South, but one great fellowship of love throughout the whole, wide world…

May I say that it is indeed an honor to be in this city, which stands as a symbol of the divisions of men on the face of the earth. For here on either side of the wall are God’s children, and no man-made barrier can obliterate that fact. Whether it be East or West, men and women search for meaning, hope for fulfillment, yearn for faith in something beyond themselves, and cry desperately for love and community to support them in this pilgrim journey. (See the complete speech here, a great website on African Americans GI’s in Germany).

A year before Dr. King’s visit, President John F. Kennedy’s motorcade had also passed the Wall, but the President did not cross to the other side. He did address a crowd of thousands in front of West Berlin’s city hall. West Berliners loved him for representing American largesse and power and for assuring them of continued US support. His iconic statement Ich bin ein Berliner (I am a Berliner) not only ignited thunderous applause, it became a legendary catch phrase of Cold War politics.

Dr. King’s words are not Cold War sound bites. They are timeless.