Earlier this month, a tattered copy of the first edition of the Communist Manifesto was sold by Sotheby’s auction house for $39,600. The price was about double what Sotheby's had expected for the 8-by-5 1/2-inch work by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The Manifesto’s first edition, written in German, was published in London in 1848, 170 years ago. The first American translation was published in Chicago forty years later, in 1888. Copies sold for a mere 5 cents, so the Sotheby sale marks an impressive value increase.

Of course, the Communist Manifesto is not about the price it fetches but about the influence it has wielded. According to Sotheby's, it has been published in every European, Asian and African language, through 736 editions. In terms of publication numbers, the Manifesto is exceeded only by the Holy Bible. As we know, the Manifesto inspired action; political movements, revolution, reaction. It also incited repression and violence on the Left and the Right.

Many people are surprised to find out that the Communist Manifesto is actually a pamphlet. Its first edition numbered only twenty-some pages and half of those are devoted to descriptions of in-fighting among the various European Socialist Parties in Marx and Engels’ times. Page for page, this slim volume has packed more punch than any other political writing. The Manifesto has built courage in some people and it has struck fear into the heart of others.

Marx and Engels’ scathing description of capitalism’s essential nature is one reason why the word capitalism is rarely used to describe our current economic system. Invisible hand, laissez faire, free market sound more cheery; simply saying the economy claims an inevitability that the Manifesto challenges. In this country, using the term capitalism to describe the economy is in itself a radical act.

Back in 1848, the Communist Manifesto predicted that the structures and values of capitalism would spread across the globe. Consider these quotes (In their writing, Marx and Engels use the terms bourgeoisie and capitalism interchangeably).

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere.

The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world-market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country…it has drawn from under the feet of industry the national ground on which it stood. All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed… In place of the old wants, satisfied by the productions of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant lands and climes.

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all…nations into civilization. The cheap prices of its commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls…it compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production… In a word, it creates a world after its own image.

This prescient description of globalization was written in the era of steam engine travel.

Marx and Engels argued that capital – or property -is not only a personal matter; it is a social power. To break up this power that is by definition the root of inequality, all private property, including rights of inheritance, must be abolished. Anticipating the outcry of property holders, they write:

You are horrified at our intending to do away with private property. But in your existing society, private property is already done away with for nine-tenths of the population; its existence for the few is solely due to its non-existence in the hands of those nine-tenths.

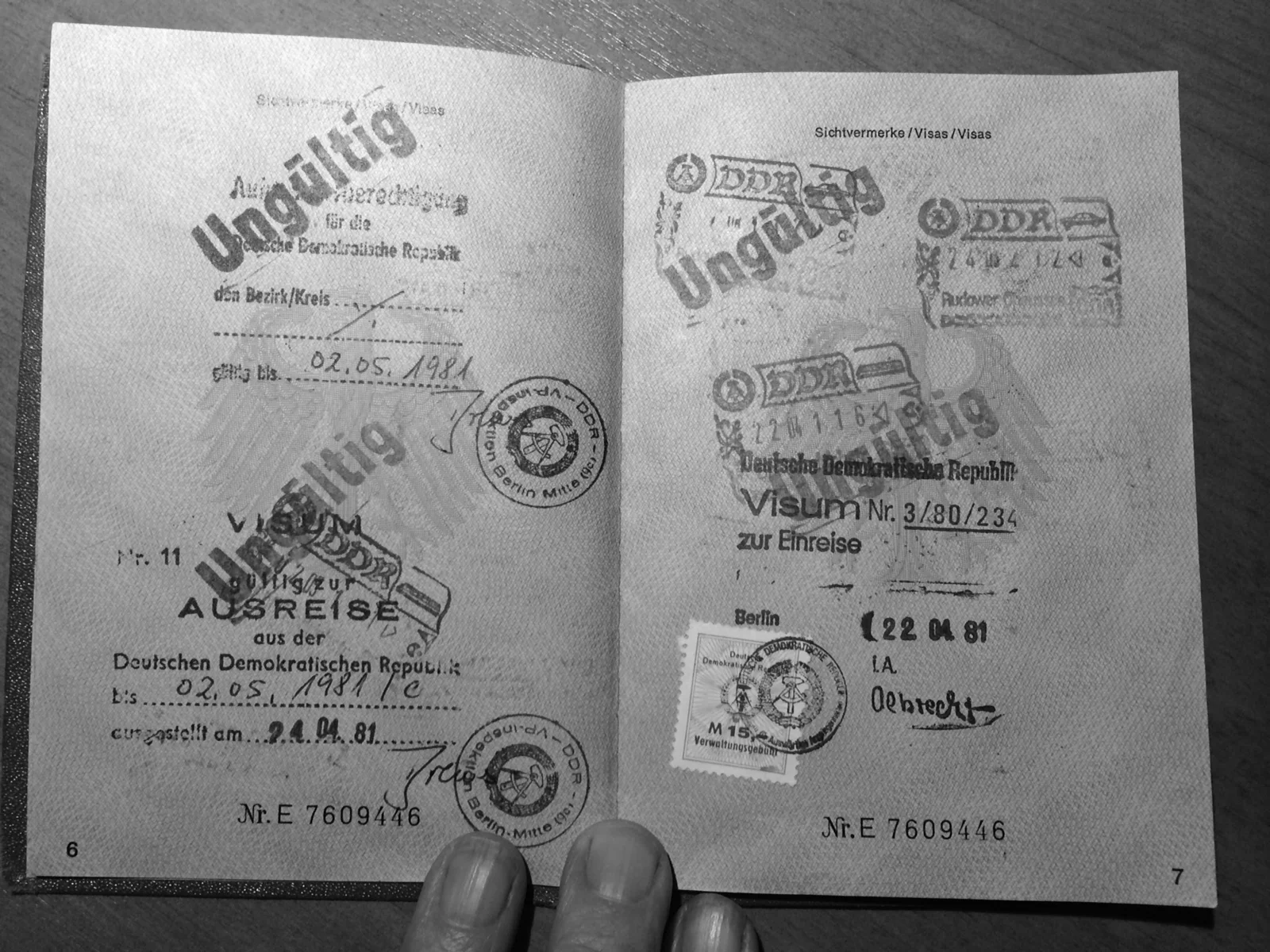

Their radical proposals struck fear into the hearts of the powers that be. Back in 1848, German state censors seized and destroyed many of the copies of the Manifesto that were imported from London.

Yet the Manifesto promises that all people will be better off in a world without private property.

In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.

It also envisions warfare becoming obsolete once private property is abolished:

In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end.

Marx and Engels’ vision of free association and a world without war didn’t alleviate the fears of capitalists. But the Manifesto’s call to action has resonated with millions around the world:

The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working Men of All Countries, Unite.

As a product of the Age of Reason, The Communist Manifesto is based on the belief that intellectual knowledge guides human actions. It doesn’t mention the emotions that move us - not fear, not love. It doesn’t anticipate feminism, racism, sexual orientation, gender, identity politics or intersectionality. Obviously, the complexity of human affairs and individual motivation could not be addressed adequately in twenty-some pages. Still, the pamphlet stands as a reminder that bold vision has great power.

Marx and Engels would probably be disheartened to know that their political tract has been purchased by a private collection for thousands of dollars. No doubt they’d rather see their Manifesto in the hands of ordinary people and their ideas shaping political discourse.